by Prof. Sher Muhammad Garewal

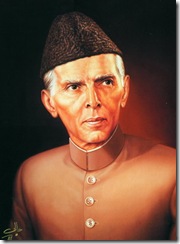

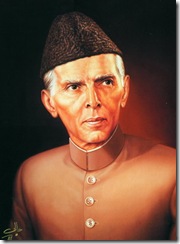

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948) was one of the most striking fascinating and remarkable personalities of modern world history. Possessed of excellent qualities of pen, mind and heart, he played a very significant role in changing the course of history and destinies of men in South Asia, having immense impact on the world history which scholars and historians have not yet full realised. The American writer Stanley Wolpert’s most quoted remarks1 do not fully convey the real significance of the Quaid’s role in modern history. The fact is that the Quaid’s role was more significant than that has been described by Wolpert. He did not only create a nation state on the basis of Muslim separatism in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, he also struggled hard to build it on strong footings as is evident from his dynamic role as the first Governor-General of Pakistan. Despite his rapidly declining health he assiduously worked and endeavoured his best for introducing basic reforms and giving guide-lines in each sector of Pakistan’s polity and society.2

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948) was one of the most striking fascinating and remarkable personalities of modern world history. Possessed of excellent qualities of pen, mind and heart, he played a very significant role in changing the course of history and destinies of men in South Asia, having immense impact on the world history which scholars and historians have not yet full realised. The American writer Stanley Wolpert’s most quoted remarks1 do not fully convey the real significance of the Quaid’s role in modern history. The fact is that the Quaid’s role was more significant than that has been described by Wolpert. He did not only create a nation state on the basis of Muslim separatism in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, he also struggled hard to build it on strong footings as is evident from his dynamic role as the first Governor-General of Pakistan. Despite his rapidly declining health he assiduously worked and endeavoured his best for introducing basic reforms and giving guide-lines in each sector of Pakistan’s polity and society.2

The Quaid, in fact, was very optimistic about the brilliant future of Pakistan. He did want to make Pakistan an exemplary Islamic welfare state. He did stand for introducing Islamic system of government in Pakistan. But it is matter of great regret that some Pakistani scholars and critics still maintain that the Quaid was least concerned with the Islamic system of government. Instead, he stood, in their opinion, for a secular system of government in Pakistan. For example late Justice Muhammad Munir, while writing his book on Pakistan toward the end of 1970’s asserted that “there can be no doubt that Jinnah was a secularist”3 and “The pattern of government which the Quaid had in mind was a secular democratic government.”4 Similarly, Rahat Saadul Kairi, while writing his book on Quaid-i-Azam in the mid ninties also claimed that Jinnah never wanted to make Pakistan an Islamic state.5 “His idea of Pakistan” says he “was of a modern, liberal, secular and democratic state.”6 This is fundamentally a wrong conception. This is rather an attempt to besmear and tarnish the Quaid’s fair image by distorting facts.

The assertions made by M. Munir and S.R. Khari are merely based on speculations and not on solid grounds. The Quaid’s speeches and statements given in support of these assertions have been generally misconstrued. Particular the Quaid’s well-known speech in the newly established Pakistan Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947 on which these critics mainly base their arguments,7 has been absolutely misinterpreted by them. The speech in question was a policy statement, emphasising some basic issues faced by the newly born state of Pakistan. The Quaid made the Constituent Assembly to realise its new position, status and responsibilities. Secondly, he laid emphasis on the eradiction of social evils such as bribery and corruption, jobbery and nepotism, hoarding and black-marketing then prevailing in the country. Thirdly, he put stress on forging equality, fraternity and unity among all sections of Pakistani society, by ending all racial and religious differences, without which Pakistan’s progress was not possible.8

A careful and deep study of this speech shows that the Quaid was not propounding any sort of secularism by advising particularly the religious sections of the people to bury their past in order to live together peacefully as good citizens of the newly-born state of Pakistan.

In fact, the situation in which the speech was made must be borne in mind. No doubt, Pakistan had been established. But the anti-Pakistan forces were fully at work to destroy it at the shage of its very inception. The communal feelings were tense, emotions ran high, resulting in horrible communal riots and massacres at a very large scale. The most parts of the subcontinent were in the grip of civil war. The Muslim villages, mohallas, towns and cities were burning: the people were passing through rivers of blood and fire. The Sikh, Hindu and British Neroes were rejoicing.9

In the midst of such grave and horrendous circumstances the Quaid’s speech was definitely a message of hope and peace. Its contents and tenor clearly indicate that it was mostly meant to cool down the exasperated communal feelings on both sides of the border, which was certainly statesman-like performance on the part of the Quaid.10 He was not discarding the two nation theory by saying that “the Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims.” These remarks did not mean that both the Hindus and the Muslims would lose their separate identities. Simply both were urged upon to work together for Pakistan as its equal citizens. If these remarks meant otherwise even then it makes no differences as the marks seem purely of a temporary nature and were never repeated by the Quaid in his subsequent speeches and statements. Likewise, the Quaid was not negating any ideological basis of Pakistan by saying: “If you (Hindus and Muslims etc.) will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in spirit that everyone of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed; is first, second and last a citizen of this state with equal rights, privileges and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make.”11 Again, the Quaid was not deviating from any basic principle of Islamic ideology while assuring religious freedom to all Pakistanis, remarking: “You are free. You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan.”12

The fact is that speaking in such terms, the Quaid was not violating any tradition or norm or principle of Islam. He was actually acting according to the injunctions of the Holy Quran.

The Holy Quran is not in favour of using force in converting peoples to Islam. It categorically says, “There is no compulsion in Islam.”13 The Holy Quran has equal consideration for the places of worship of the peoples of different faiths. In the course of discourse, it clearly remarks: “For had it not been for Allah’s repelling some men by means of other, cloisters and churches and oratories and mosques, wherein the name of Allah is oft mentioned would assuredly have been pulled down. Verilly Allah helpeth one who helpth Him.”14 Granting freedom of worship to the peoples of different faiths in Pakistan, the Quaid, in fact, was serving the purpose of the Holy Quran.

Besides, the Quaid was following in letter and spirit the Hoy Prophet’s (Peace be upon him) commands such as “Beware! Whosoever is cruel and hard on such people (i.e. contractees) or curtails their rights, or burdens them with more than they can endure, or realises any thing from them against their free will. I shall myself be a complainant against him on the day of judgement.”15

Further more, the Quaid was really following the principle and traditions set up through treaties by the Holy Prophet and the Pious Caliphs regarding the equal treatment with the non-Muslims. Some relevant lines particularly of the famous treaty made by Hazrat Umar (15 A.H.) with the non-Muslims of Jerusalem may be noted here:

The protection is for their lives and properties, their churches and crosses, their sick and healthy and for all their co-religionists. Their churches shall not be used for habitation, nor shall they be demolished, nor shall any injury be done to them or to their compounds, or to their crosses, nor shall their properties be injured in anyway. There shall be no compulsion on them in the matter of religion, or shall any of them suffer any injury on account of religion.16

The non-Muslims really enjoyed equal rights and status with Muslims in the Islamic state. Their lives, properties and places of worship were considered as sacred as those of the Muslims.17 And the Quaid was fully aware of the spirit of all these and such other Islamic teachings, principles and traditions: he could not be expected to injure the feelings of the non-Muslims in his very inaugural speech. Of course, as a just and benevolent ruler and founder of a new nation, he spoke and spoke masterly using the idiom and expression of civilized founders of dynasties or nations or empires in history.

Like his inaugural speech in the Constituent Assembly, some of his interviews with foreign correspondents, broadcast talks to the world nations and official address in the formal meeting occasionally arranged by certain foreign embassies have also been misunderstood and mis-interpreted. No doubt, in such interviews, talks and addresses, the Quad had to speak but delicately, formally and diplomatically, even some time admiring some foreign system of government.

For example replying to the speech of the first ambassador of the Republic of France to Pakistan on April 9, 1948, the Quaid formally remarked, “In common with other nations, we in Pakistan have admired the high principles of democracy that form the basis of your great State.”18 But this and such other formal and diplomatic statements do not present him as a “secularist” or as a supporter of the establishment of any Western system of government in Pakistan. The Quaid preferred Islamic democracy to Western democracy, as is evident from his pronouncement. Addressing some naval officials at Malir on February 21, 1948, he observed:

You have fought many a battle on the far-flung battlefields of the globe to rid the world of the Fascist menace and make it safe for democracy. Now you have to stand guard over the development and maintenance of Islamic democracy. Islamic social justice and the equality of manhood in your own native soil.19

Anyhow, before going further, we must understand these questions. What is a secularist? What is secularism? What is western or modern democracy, after all?

In the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, a secularist has been described as “an adherent of secularism”20 while about secularism the same dictionary records, “The doctorine that morality should be based solely on regard to well-being of mankind in the present life, to the exclusion of all considerations drawn from belief in God or in future state.”21 It means that a secularist is a person who does not believe in God and the world hereafter. Commonly such a person is called atheist.

The fact is that the Quaid was not a secularist. On the contrary, he was a staunch Muslim, a great believer in God, a true lover of the Holy Propher (peace be upon him), an enthusiastic supporter and exponent of Shariat laws as is evident from his whole historic background.

We know it well that he joined Lincoln’s Inn because there, on the main entrance, the name of the Prophet was included in the list of the great Law-givers of the world.”22 He spoke of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), as a great statesman and a great sovereign.23 “His appreciation of the Prophet” (peace be upon him) writer Hector Bolitho, “was realistic perhaps his political conscience, as a Muslim, had already begun to stir, while he was in England.”24 So much so that at a very early stage he had started his public career by attending the meetings of Anjum-i-Islam of Bombay which definitely stood for the promotion and protection of Muslim rights.25 And later on as a lawyer and legislator, he took great interest in safeguarding and promoting the Sharia laws. His role in piloting the well-known “Mussalman Wakf Validating Bill” on March 17, 1911, in the Imperial Legislative Council, and then constantly and single-handedly working for its ultimate enactment in March, 1913, was really one of the most glaring achievements in the very beginning of Quaid’s public career.26 Similarly in the subsequent years he continued to serve the cause of Islam.27 The Quaid, in fact believed in oneness of God, Prophet and Muslim millat. He repeatedly expressed it in the course of his speeches and statements. On one occasion he said: “We Mussalmans believe in one God, one Book – the Holy Quran – and one Prophet. So we must stand united as one Nation.”28 Likewise on another occasions he spoke thus, “It is the Great Book, Quran that is the sheet-anchor of Muslim India. I am sure that as we get on and on there will be more and more oneness – One God, one Book, one Prophet, and one Nation.”29 The fact is that the Quaid was a great admirer of Islam, its tenets as well as its government system while on the contrary, he was a great critic particularly of the Western parliamentary system of government.

But what is the spirit and meaning of the Western democracy? Theoretically, the Western democracy has been generally considered as the government of the people by the people for the people. But in words of the Quaid western democracy did not exist anywhere in the world in the strict sense of the word.”30 On the contrary, it widespread use and application to every sort of government and institution has confused its initial spirit and meanings. No wonder if the western intellectualism has failed to properly define the term modern democracy. “Discussion about democracy”, records the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, are intellectually worthless because we do not know what we are talking about.”31 Hence democracy, the same source records” is harder to pin down.”32 Even the British parliamentarian of the calibre of Winston Churchill (1875 – 1965) bitterly criticised democracy. He remarks, “Democracy is the worst possible form of government except all others that have been tried.” 33

Whatever the case may be, the Quaid was a great critic of western democracy, even though he himself worked under this system in undivided India. He often criticised it in the course of his speeches in the Legislative Assembly debates.34 He bitterly spoke against it during the proceedings of the Round Table Conferences (1930-32).35 Besides, in his well known article on “The Constitutional Maladies in India” published in the Time and Tide (London) in January 1940 he strongly criticised the ills of the western democracy and rightly considered it as most unsuitable to united India.36 Speaking in a meeting of the Muslim University Union Aligarh, on March 10, 1941, he observed,“ I have asserted on numerous occasions that democratic parliamentary system of government they have in England and other western countries is entirely unsuited to India.”37 Because western democracy means majority rule and in undivided India it meant a Hindu rule as the Hindus were in a perpetual majority which was surely not in the interest of the Muslims who were in a perpetual minority. Speaking on the occasion of the historic session of All-India Muslim League held at Lahore in March, 1940, when the Lahore resolution was passed, the Quaid “exposed the barren and absolutist character of democracy which the Congress High Command wished to impose on the whole of India. This, in his opinion, would “only mean Hindu Raj” and “the complete destruction of what is most precious of Islam.”38

Not to speak of the Quaid, no sensible Muslim leader could favour the introduction or application of any western system of democracy in India. Otherwise, it would have been a complete negation of Muslim separatism on the basis of which a separate, independent and sovereign Muslim state was demanded.

The Quaid wanted to establish a free Muslim state in order “to develop to the fullest our spiritual, cultural, economic, social and political life in a way that we think best and in consonance with our ideal and according to the genius of our people.”39 While addressing the Muslim University Union, Aligarh in March 1941, the Quaid stressed that Pakistan was the only solution of the Indian problem “if you want to save Islam from complete annihilation in this country.”40 The Quaid quite clear in his mind. “Let me live”, he said to Hindus in November 1942, “according to my history in the light of Islam, my tradition, culture and language, and do the same in your zones.”41

The Quaid indeed wanted to introduce Islamic system of democracy in Pakistan. Speaking in the meeting of the All-India Muslim League Working Committee held in Delhi in March 1943, the Quaid, while replying to a controversial point with regard to “the future system of government, maintained that “We want a Muslim homeland wherein the Muslims will be free to choose their own government and conduct their affairs according to their tradition and genius, driving inspirations from the fundamental principles of Islam, based on brotherhood, equality and fraternity of man.”42

The point under discussion can be further elaborated by referring to one Maulvi Muhammad Munawarruddin’s meeting with the Quaid in March 1943, years before independence Maulvi Sahib discussed with the Quaid the system of government to be introduced in Pakistan after its birth. After the meeting M.S. Toosy, a close associate of the Quaid inquired from Manuwaruddin about the discussion. “His conclusion”, says Toosy, “was that when Pakistan would be established, the Quaid-i-Azam would enforce the laws of Shariat and the Constitution would be framed according to the Islamic principles based on the Quran.”43

Explaining the creed of Pakistan to Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan early in 1943, the Quaid said that Pakistan would be based where we will be able to train and bring up Muslim intellectuals, educationsits, economists, scientists, doctors, engineers, technicians etc. who will work to bring about Islamic renaissance.”44 After necessary training, they would spread to other parts of the Islamic world “to serve their co-religionists and create awakening among them eventually resulting in the creation of a solid, cohesive bloc – a third bloc – which will be neither communistic nor capitalistic but truly socialistic based on the principles which characterized Caliph Umar’s regime.”45 In a message of to the NWFP Students Federation on April 4, 1943 he said: “You have asked me to give you a message. What message can I give you? We have got the greatest message in the Quran for our guidance and enlightenment.”46

Again in April 1943, Abdul Waheed Khan, a member of the All-India Muslim League, addressed a letter to the Quaid and requested him to clarify the object of Pakistan in his presidential address at the session of the Muslim League which was due to be held in the next few days. In his own view this object was not only to free the Mussalmans of certain parts of India but to liberate Islam, its traditions, its systems of law and above all, its social and economic order. Islamic rule means the Kingdom and sovereignty of God, and not of Mussalmans over the non-Muslims.47 The Quaid in his speech on April 24, at Delhi said: “Please substitute love for Islam and your nation, in place of sectional interest.”48 He held out a firm assurances that the government of the proposed state of Pakistan would be democratic and people’s government” and its constitution will be framed by the Millat. He believed that “democracy is in our blood. It is in our marrows. Only centuries of adverse circumstances have made the circulation of that blood cold.”49 As regards the social and economic order in an Islamic state, he was clear and forthright, “Here I should like to give a warning to the landlords and capitalists who have flourished at our expense. They have forgotten the lessons of Islam…There are millions and millions of our people who hardly get one meal a day. Is this civilization? Is the aim of Pakistan….If that is the idea of Pakistan, I would not have it.”50 Touching upon the question of minorities he ruled out all “intentions of domination”. ”Minorities”, he said, “must be protected and safeguarded to the fullest extent….Our Prophet has given the clearest proof that non-Muslims have been treated not only justly and fairly but generously.”51

At the Karachi session of the Muslim League in December, 1943, Nawab Bahadur Yar Jang, whom the Quaid-i-Azam held in highest esteem, said: “There is no denying the fact that we want Pakistan for the establishment of the Quranic system of government. It will bring about a revolution in our life, a renaissance, a new Islamic purity and glory.”52 In his concluding remarks he said that Islam was the bedrock of the community. “It is the Great Book, the Quran, that is the sheet-anchor of Muslim India”. He said, “I am sure that as we go on, there will be more and more oneness – one God, one Book, one Qibla, one Prophet and one nation.”53

The Holy Quran was the Quaid’s source of inspiration and his guidance. It sustained him in the darkest moments of his life. “Why should we worry or be dejected,” he once told Mian Bashir Ahmad, “When we have got this great Book to guide us”54. “Its teachings”, he added, “are not restricted to religious and moral issues, it is a comprehensive code of life. A religious, social, civil, commercial, military, judicial, criminal, penal code”, he said on later occasion, “it regulates everything from the ceremonies of religion to those of daily life; from the rights of all to those of each individuals; from morality to crime, from punishment here to that in the life to come.”55

Addressing the students of Islamia College, Peshawar, he categorically announced: “The League stood for carving out stages in India where Muslims are in numerical majority to rule here under Islamic law.”56

On the eve of the inaugural session of the Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Islam at Calcutta in November, 1945, Maulana Ghulam Murshed, the Imam of Badshahi Mosque, Lahore, met Quaid-i-Azam and received a definite assurance from him that the injunctions of the Holy Quran alone would be the basis of law in the Muslim state.57 In a letter to the Pir Sahib of Manki Sharif in November 1945, the Quaid said, “it is needless to emphasise that the Constituent Assembly which would be predominantly Muslim in its composition, would be able to enact laws for Muslims, not inconsistent with the Shariat laws, and the Muslims will no longer be obliged to abide by the unIslamic laws.”58 In a meeting with Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani in June 1947, the Quaid assured him that an Islamic constitution would be implemented in Pakistan.59

It may perhaps be said that all these assurances or pronouncements of the Quaid belong to a period before the emergence of Pakistan. It may, therefore, be argued that it was scarcely anything more than a familiar device, on the part of a politician who used Islamic vocabulary to bring the maximum number of Muslims in the fold of the Muslim League.60 This line of reasoning is supported by assertion that the Quaid dropped all references to Islam and Islamic state in his post Independence speeches. Sir Parkas, the first Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan, tried to strengthen this view by reporting a conversation between himself and the Quaid-i-Azam soon independence. “I know”, he reportedly said to the Quaid, “that Partition has been effected on the basis of differing religions. Now that this has taken place, I see no reason why stress should be laid on Pakistan being Islamic State…At this he (Quaid-i-Azam) said that he had never used the word ‘Islamic’.61 This fanciful story stands clearly discredited in the face of numerous post-independence speeches of the Quad. Indeed, he was even more forthright on the subject of loyalty to Islam and its principles.62

The fact is that even after the creation of Pakistan, the Quaid became more vocal and persistent for adopting Islamic way of life and system of government in Pakistan. Outlining the purpose of the creation of Pakistan, the Quaid-i-Azam said in a speech to the officers of the Defence Service on October 11, 1947 that the establishment of Pakistan was only a “means to an end and not the end in itself. The idea was that we should have a state in which we could live and breathe as free men and which we could develop according to our own lights and culture and where principles of Islamic social justice could find freeplay”.63 Addressing a public meeting in Lahore a few days later, he described the circumstances in which Pakistan came into existence. Consoling those who had been subjected to inhuman brutalities as a result “of a deeply laid and well-planned conspiracy” on the part of the enemies of Pakistan, he gave them the hope that this was but a temporary setback. He assured them that “if we take inspiration and guidance from the Holy Quran, the final victory, I once again say, will be ours.” He advised that everyone “to whom this message reaches must vow to himself and be prepared to sacrifice his all, if necessary, in building up Pakistan as a bulwark of Islam. Do not be afraid of death…Save the honour of Pakistan and Islam.”64

In January, 1948, at a reception on the occasion of the Holy Prophet’s birth anniversary, he declared that “he could not understand a section of the people who deliberately wanted to create mischief and made propaganda that the constitution of Pakistan would not be made on the basis of Shariat”. He reminded his audience that “Islamic principles today are as applicable to life as they were 1,300 year ago”.65 Paying his humble tributes to the Holy Prophet he said: “not only has he reverence of millions but also commands the respect of all the great men of the world… The Prophet was great teacher. He was a great law-giver. He was a great statesman and he was a great sovereign who ruled. No doubt there are many people who do not quite appreciate when we talk of Islam.66 “Islam is not a set of rituals, traditions and spiritual doctrines. Islam is also a code for every Muslim which regulated his life and his conduct in even politics and economics and the like….In Islam there is no difference between man and man. The qualities of equality, liberty and fraternity are the fundamental principles of Islam.”67

Speaking on a reform scheme at Sibi Darbar on February 4, 1948 remarked:

In proposing this scheme, I have had one underlying principle in mind, the principle of Muslim democracy. It is my belief that our salvation lies in following the golden rule of conduct set for us by our great law-giver the Prophet of Islam. Let us lay the foundations of our democracy on the basis of truly Islamic ideals and principles.68

In a broadcast talk to the people of Australia, on February 19, the Quaid spoke of the Islamic characteristics of Pakistani society in these words:

The great majority of us are Muslims. We follow the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). We are the members of the brotherhood of Islam in which all are equal in rights, dignity and self-respect. Not only are most of us Muslims but we have our own history, customs and traditions and those ways of thought, outlook and instinct who go to make up a sense of nationality.”69

In a similar talk to the people of the United States of America in February 1948, he spoke of Islamic system of government to be adopted in Pakistan.

The constitution of Pakistan has yet to be framed by the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. I do not know what the ultimate shape of this constitution is going to be, but I am sure that it will be of a democratic type, embodying the essential principles of Islam. Today they are as applicable in actual life s they were 1,300 years ago. Islam and its idealism have taught us democracy. It has taught equality of man, justice and taught us democracy. It has taught equality of man, justice and fairplay to every body. We are the inheritors of these glorious traditions and are fully alive to our responsibilities and obligations as framers of the future constitution of Pakistan.70

Now we can certainly say that the Quaid was neither a secularist nor a socialist nor an admirer and up-holder of western or modern democratic system of government. Instead, he was a great Muslim. He believed in Islam and its democratic system of government.

But what is Islamic democracy or Islamic system of government, after all? Islamic democracy is actually a system of government in which sovereignty belongs to Allah the affairs are conducted by elected Caliph or a Head of the Islamic state according to Shariah with the help of an advisory Council (Majlis-i-Shura). The Public opinion is respected and honoured but Shariah prevails in each and every matter of Islamic state. It can be further elaborated in the words of the Quaid.

Fundamentally, in an Islamic state, all authority rests with Allah, the Almighty. The government business is conducted according to the entire Quranic principle and injunctions. Neither a head, nor a parliament, nor an individual, nor an institution can act absolutely in any matter. Only the Quranic injunction control our behaviour in society and politics. In other words the rule of Islamic democracy is indeed the rule of Shariat laws.71

The Quaid did believe in Islamic democracy, and not in theocracy which had no concern with Islamic democracy. While introducing Pakistan to the people of Australia he had categorically remarked, “But make no mistake, Pakistan is not a theocracy or anything like it."72

Theocracy indeed both as a concept or a system is purely a western product.73 Not to speak of Quaid’s views in this respect, even the scholar of the calibre of Maulana Maududi does criticize the concept of theocracy and denies its existence in Islamic system of government.74

Furthermore the Quaid launched the Pakistan movement simply and purely on the basis of Islamic ideology. But some of the critics also maintain that Quaid never used the term Pakistan ideology in his speeches and statements. On the contrary, the fact is that the Quaid was very much the exponent of Pakistan movement days, he maintained: “Our religion, our culture, and Islamic ideals are our driving force to achieve independence.”75 Addressing the All-India Muslim League session at Madras in 1941, the Quaid said: “The ideology of the League is based on fundamental principle that Muslim India is an independent nationality.”76 Similarly in a message to the Frontier Muslim Students Federation (June 15, 1945) the Quaid spoke thus: “Pakistan not only means freedom and independence but the Muslim ideology which has to be preserved.”77

The fact is that whenever he happened to define and explain Pakistan’s aim and objective, he often used the terms “Muslim Ideology”, “Muslim League” which later came to be known as Pakistan ideology which is simply the result of evolutionary historical process in which things, words and terms may adopt different forms with different meanings, when in any historical process of events, episodes and revolutions mostly take their name after their actual occurrences in history. The terms of the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution came into use only after the revolutions, actually took place (respectively in 1798 and 1918), and not before that. So the term “Pakistan Ideology” is definitely the product of history and not the handiwork of any particular group or party as is maintained by the critics.”78

Nevertheless, the Quaid was a great exponent of Pakistan ideology which he equated to Islamic ideology. He fully understood Islam and its teachings, traditions and principles of toleration, social justices, democracy, equality, fraternity and polity. He believed in its utility and practicability in modern age. But he maintained that the Islamic principles could not be fully realised without a state. So during the Pakistan movement days he often spoke on such lines: “We want a Muslim homeland wherein the Muslims will be free to chose their own government and conduct their affairs according to their own tradition and genius, deriving inspiration from the fundamental principles of Islam based on brotherhood, equality and fraternity of man.”79

And that Muslim homeland – Pakistan – was achieved on the basis of Islamic ideology. The Quaid was happy and proud of that most brilliant achievement which he always saw in terms of Islam. In his speeches and statements, he often proudly pronounced Pakistan as the “biggest Islamic state,”80 He wanted to build it up as a “bulwark of Islam.”81

Now in the light of above discussions we can safely conclude that the Quaid really wanted to establish Islamic democratic system in Pakistan. His vision was very clear in this respect.82 Unfortunately, his untimely death in September, 1948 hardly a year after the establishment of Pakistan, did not allow him to achieve his cherished aims. Otherwise, he was definitely determined to make Pakistan purely an Islamic welfare state. His bonafides could not be suspected. He was a man of character and integrity. Throughout his life, what he said he meant it – a fact which could not be denied even by his greatest opponent, M.K. Gandhi (1869-1948), who had certainly the highest regard for Quaid’s single-mindedness, his great ability and integrity.”83

But it is matter of great regret, that critics like Justice Munir and S.R. Khairi could neither understand Quaid-i-Azam nor they could comprehend Islam, otherwise their approach to the subject under discussion would have been certainly positive one.

Notes and References

- The remarks read, “Few individuals after the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three. Jinnah of Pakistan (New Delhi, Vikas Publications, 1985, p. vii). But strangely enough, Wolpert, speaking in the same breath, mars the value of these remarks by remarking the Quaid as an enigmatic personality like Gandhi (Ibid.), which is absolutely a wrong thesis. Weigh him by any standard of historical criticism, the Quaid will stand as a just, straightforward and far-sighted statesman and not a complicated and enigmatic politician as Wolpert maintains. “Jinnah was not as complex a character as it is made out” S.R.Khairi; p. xv (Full reference under Foot Note No. 5).

- Sher Muhammad Garewal, “Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah” Urdu Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. 19, pp. 461-92, Gul-e-Rana, “Quaid-i-Azam’s Role as Governor-General” unpublished M.A. thesis submitted to the University of the Punjab in 1979.

- From Jinnah to Zia (Lahore, Vanguard Books, 1979), p. vii.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- Saad R. Khairi, Jinnah Reinterpreted: The Journey from Nationalism to Muslim Statehood (Karachi, Oxford University Press, 1995) pp. Vi-xx.

- Ibid., p. 459.

- Muhammad Munir, op. cit., pp. Vii, 29-30, Saad R. Khairi, op. cit, pp. Xviii-xix.

- Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah; Speeches as Governor-General 1947-48. (Karachi, Pakistan Publication, n-d) pp. 7-9.

- See, Ch. Muhammad Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan, (Lahore, Researc Societh of Pakistan, 1973): Leonard Mosley, The Last Days of the British Raj (Lahore, Urdu Digest Publications, 1973): Jamiluddin Rizvi, Pakistan Story (Lahore, 1973): Khushwant Singh, Train to Pakistan (London, 1954), Khawaja Iftikhar, Jab Amritsar Jal Raha Tha, (Lahore, 1981)

- Fateh Naseeb Chaudhri, Quaid-i-Azam Ka Taswwar-i-Mumlukat-e-Pakistan (Lahore, Pakistan Study Centre, Punjab University, 1985) pp. 13-14; Also see Prof. Waheed uz-Zaman, “The Quaid-i-Azam’s vision of Pakistan”, The Pakistan Times, August 14, 1979, p, iii: “The Quaid’s speech”, remarks Prof. Waheed-uz-Zaman also, needs…to be read in the context of the prevailing political situation which vitally affected not only the security but even the continued existence of the nascent state of Pakistan. Since a climate of total insecurity prevailed on both sides of the border and one of the greatest mass migrations in the history of mankind had had already started, such an assurance to the non-Muslims of Pakistan was urgently called for. It would, the Quaid hoped, not only stop the exodus of Hindus from Pakistan but would also have salutary effect on Indian leaders and persuade them to extend similar treatment to the Muslim minority in India.

- Speeches as Governor-General, op cit.. p. 8.

- Ibid., pp. 8-9.

- Al-Quran, II, 256.

- Al-Quran, XXII-40.

- Abu-Daud, the Book of Jihad cited by Abdul Ala Maududi, in his books, Islamic Law and Constitution (Lahore, Islamic Publications, 1960), p. 300.

- Zafar Ali (Trs), Omar the Great by Maulana Shibli Nomani, Vol. II. (Lahore, Muhammad Ashraf, 1976) p. 165.

- Ibid., pp. 184-86; Abul Ala Maududi, The Islaic Law and Constitution (Lahore, Islamic Publications, 1960), pp. 292-321; The Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. II Leiden, 1961) pp. 227-30.

- Speeches as Governor-General 1947-48, op cit, P. 108.

- Ibid., p. 61.

- Ibid., Vol. II, ed. 1973, p. 1926.

- Ibid.

- Cited by Hector Bolitho, Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan. (London, Co-Wyman, Reprint, 1960), p. 9.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Riaz Ahmad, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Formative Years 1892-1920 (Islamabad, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, 1986) p. 62.

- Ibid., p. 89, The Works of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: The Formative Years 1892-1920 (Islamabad, Chair on Quaid-i-Azam, Quaid-i-Azam University 1996) pp. 297-302.

- And during the Pakistan Movement days, he had developed a special interest in the historical literature of Islam. According to M.S. Toosy, he had in his library book on Islamic history, life of the Holy Prophet, and other great men of Islam, and translations of the Holy Quran. He had studied English translations of Al-Farooq (Life of Caliph Umar), which was written by Maulana Shibli Normani and translated by Maulana Zafar Ali Khan. He wanted to read the second part of this book dealing with administration and reforms of the Caliph Umar but its English translation was not available.

- Quaid-i-Azam as Governor General, op. cit., p. 126.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, Speeches and Writings of Mr. Jinnah, Vol. I. (Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1968), p. 597.

- Ibid., p. 226.

- Vol. 4. ed. 1968, pp. 112-20.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jamiluddin Ahmed, Vol 3, I &II.

- See, The Proceedings of the Round Table Conferences 1930-32. Riaz Ahmad, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Second Phase of his Freedom Struggle 1924-1934 (Islamabad, Chair on Quaid-i-Azam and Freedom Movement, Quaid-i-Azam University 1994) p. 124-50.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, Vol. I, op. cit., pp. 122-133.

- Ibid., p. 248.

- Waheed-uz-Zaman, “The Quaid-i-Azam’s Vision of Pakistan. The Pakistan Times, August 14, 1979, p. III: Jamiluddin Ahmad, op. cit. p. 170.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, op. cit., P. 171.

- Ibid., p. 253.

- Ibid., pp. 458-59.

- M.S. Toosy, My Reminiscences of Quaid-i-Azam (Islamabad, Ministry of Education, Government of Pakistan, 1976) p. 48.

- Ibid., p. 53.

- Waheed-uz-Zaman, op. cit. p. iii.

- Ibid.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, Vol. I, op.cit., p. 490.

- Waheeduzzamman, op. cit., p. III.

- Jamiluddin, Vol. I, op. cit., p. 494.

- Ibid., pp. 526-27.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 527.

- Waheed-uz-Zaman, op. cit., p. iii.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., Jamiluddin Ahmad, Vol. I, op. cit., p. 209.

- Dawn, December 4, 1945.

- Waheed-uz-Zaman, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Speeches as Governor-General, op. cit., p. 22.

- Ibid., p. 29-31.

- Speeches and Statements as Governor-General, (edition, 1989), p. 125.

- Ibid., p. 127.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 56

- Ibid., p. 58

- Ibid., p. 65

- Rahbar-Daccan, August 19, 1941: Ahamd Saeed, Guftar-i-Quaid-i-Azam, (Islamabad, Historical and Cultural Research, 1976), pp. 261-62.

- Speeches as Governor-General, op. cit., p. 58

- Khurshid Ahmad, Western Fundamentalism, Khurshid Ahmad has critically examined the concepts of theocracy and fundamentalism. To him these concepts are the product of the West. Such concepts have no place in Islam.

- Abul Ala Maududi, (Lahore, Islamic Publications, 1969), p. 129: Khurshid Ahmed (Trs.): Islamic Law & Constitution (Lahore, Islamic Publications, ed 1960) pp. 147-49.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, Vol. II, op.cit. p. 242.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, Vol. I, op. cit. p. 265.

- Ibid., Vol. II, p. 175.

- Muhammad Munir, op.cit., p. 29, S.R. Khairi, op. cit., pp. 463-78.

- Jamiluddin Ahmad, op. cit., pp. 171, 174.

- Speeches s Governor General, op. cit., pp. 29, 33.

- Ibid., p. 30.

- Waheeduzzaman, op. cit., p. iii.

- See Jamiluddin, Quaid-i-Azam as seen by Contemporaries, (Lahore, Publishers United, 1966) p. 243.